Focus of this post

As many in the WordPress community will know by now thanks to Jeff Chandler’s helpful post on the case, recently Chris Pearson was unsuccessful in his complaint against Automattic regarding its purchase of the thesis.com domain name. Pearson had sought to have the domain transferred to him. I want to say a few things about this case but I’m not going to get emotional about it nor will I publish any comments that come across as hostile, abusive or potentially defamatory. My interest is to point out a few things that do not seem prominent in the discussions I’ve seen to date and to do so from a hopefully dispassionate legal perspective.

Facts

The key facts seem to be these:

- Many years ago, Chris Pearson developed a theme for WordPress called Thesis. When released, Pearson did not license Thesis under the GPL.

- In due course, there was heated if not acrimonious debate between Matt Mullenweg and Pearson as to the licensing of Thesis. Mullenweg argued that Thesis should be licensed under the GPL; Pearson argued he was not required to do so. (I’ve said a bit more about this in WordPress themes, the GPL and the conundrum of derivative works).

- At one point, it looked as though Pearson would be sued, but it didn’t come to that. Nevertheless, it seems clear that deep battle scars remained on both sides. At one point Mullenweg even appears to have offered to give Thesis purchasers a GPL premium theme of their choice at no cost. (To really understand what many believe to be the true context for this case, you need to listen to the debate between Pearson and Mullenweg on Mixergy back in 2010.)

- Eventually, in July 2010, Pearson changed the licensing for Thesis, announcing this on Twitter: “Friends and lovers: Thesis now sports a split GPL license. Huzzah for harmony! #thesiswp”

- Pearson owns registered trademarks for both “Thesis” and “Thesis Theme”, in each case for “web site development software”. These trademarks were registered in October and November 2011 and it appears that Pearson has been using the names since 2008.

- In more recent times, Automattic and Pearson were both approached by a third-party for the possible purchase of the thesis.com domain name. Automattic was the higher bidder, paying $100,000 for the domain name.

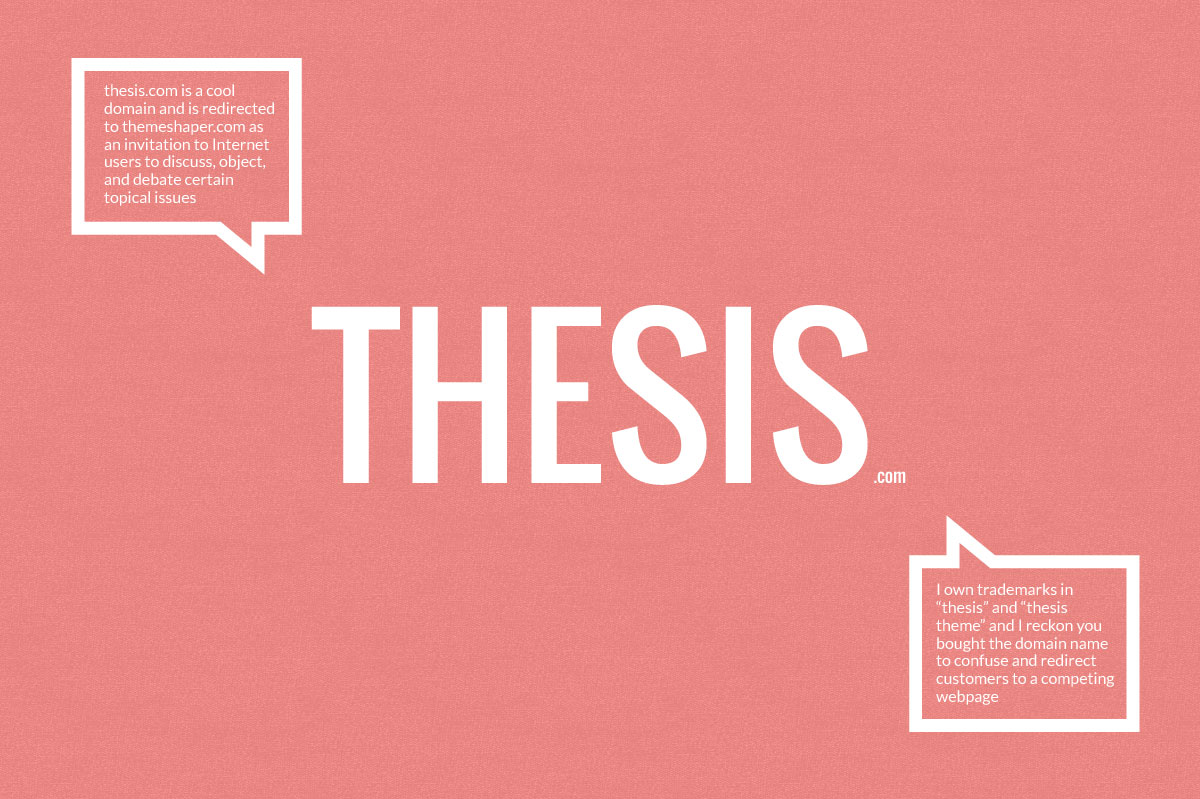

- Pearson instituted proceedings in accordance with ICANN’s Uniform Domain Name Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP). Pearson argued that he had registered trademark rights in the THESIS mark; that Automattic’s domain name thesis.com was identical to that mark (except for the top level domain name “.com” which was not relevant); that Automattic does not have any products named ‘thesis’ or offer services using the ‘thesis’ name; that Automattic’s registration of the disputed domain name, to sell competing products, likely violates Pearson’s trademark rights; and that Automattic purchased the disputed domain name to confuse and redirect customers and potential customers to Automattic’s competing webpage.

- Automattic argued, among other things, that “thesis” is a generic term; that it was using the disputed domain name in connection with a blogging site, such use serving as an invitation to Internet users to discuss, object, and debate certain topical issues and, therefore, falling within the definition of the term “thesis”; that Automattic purchased the domain name pursuant to a bona fide offering of goods under the UDRP; and that Pearson had not proven bad faith with supporting evidence (this argument was made because one of the three things a complainant must establish is that the ‘domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith’).

Decision

The Panel made these key findings:

- Pearson established legal rights and legitimate interests in the mark contained in its entirety within the disputed domain name;

- Automattic failed to submit extrinsic proof to support the claim of rights or interests in the disputed domain name;

- the disputed domain name is identical to Pearson’s legal and protected mark; and

- Pearson failed to bring sufficient proof to show that Automattic registered and used the disputed domain name in bad faith.

Now, as Jeff noted in his post, paragraph 4(a) of the UDRP requires a complainant to prove each of the following three elements to obtain an order that a domain name should be cancelled or transferred:

- the domain name registered by the respondent is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark or service mark in which the complainant has rights; and

- the respondent has no rights or legitimate interests in respect of the domain name; and

- the domain name has been registered and is being used in bad faith.

The first two elements were satisfied. Only the third was not but that is because Pearson failed to bring sufficient proof to show that Automattic registered and used the disputed domain name in bad faith.

It’s important, in my view, to look at what the Panel actually said. In relation to the second element, the Panel said this (I’ve replaced references to Complainant and Respondent with Pearson and Automattic):

“Rights to or Legitimate Interests:

…

… In the instant case the Panel finds that [Automattic] is not commonly known by the disputed domain name.

… The Panel finds that [Automattic] is using the disputed domain name to redirect internet users to [Automattic’s] competing webpage, which is not a bona fide offering of goods or service or a legitimate noncommercial or fair use of the domain name under Policy ¶¶ 4(c)(i) and 4(c)(iii). …

…

The Panel finds that [Pearson] established a prima facie case in support of its arguments that [Automattic] lacks rights and legitimate interests under Policy ¶ 4(a)(ii), which showing is light. … However, [Automattic’s] offer draws the Panel’s attention to a troublesome area. Allegedly, [Automattic] and [Pearson] were both approached by a third-party for the possible purchase of the <thesis.com> domain name, and [Automattic] was the higher bidder, paying $100,000.00 for the domain name. Such a purchase has been considered a bona fide offering of goods under Policy ¶ 4(c)(i) by past panels. … Therefore, this Panel considers that [Automattic’s] purchase of the <thesis.com> domain name for $100,000.00 could confer rights sufficient for Policy ¶ 4(c)(i) rights and legitimate interests, had adequate evidence to that effect been adduced. The Panel notes, however, that [Automattic] did not provide documentary evidence establishing this purchase of the disputed domain name for $100,000.00 and therefore the Panel declines to give that claim full credibility without such proof, which would have been easy for [Automattic] to provide and which should be [Automattic’s] burden to provide if the Panel were to rely on that claim as proof of rights.

Further, [Automattic] is purportedly using the disputed domain name in connection with a blogging site as per its Attached Exhibit (<themeshaper.com> home page). [Automattic] argues that such use serves as an invitation to Internet users to discuss, object, and debate certain topical issues. Panels have found rights and legitimate interests where a respondent was hosting a noncommercial website. … Yet, here as well, [Automattic] provides nothing more than the invitation to engage in such activities. Therefore, the Panel declines to find that [Automattic] actually operates the <thesis.com> domain name in connection with a legitimate noncommercial or fair use per Policy ¶ 4(c)(iii).

[Automattic] also argues that the term of the <thesis.com> domain name is common and generic/descriptive, and therefore, [Pearson] does not have an exclusive monopoly on the term on the Internet. Contrary to [Automattic’s] position, the appropriate authority registered THESIS as a mark and [Pearson] established those legal rights to that mark. [Automattic’s] premise is contradicted by this governmental proof of legal rights.

The Panel finds that [Pearson] has made out a prima facie case that [Automattic] lacks rights or legitimate interests in the disputed domain name and that [Automattic] has not rebutted that prima facie case. [Pearson] has therefore satisfied the elements of ICANN Policy ¶ 4(a)(ii).”

In relation to the third element, the Panel said (among other things) this:

[Pearson] claims that [Automattic’s] use of the disputed <thesis.com> domain name is to divert and confuse customers and potential customers. The Panel notes that [Pearson] did not include an exhibit showing that <thesis.com> redirects to a webpage owned by [Automattic]. The Panel suggests that the submissions might point toward use by [Automattic] that would support findings of bad faith, pursuant to Policy ¶ 4(b)(iv) if evidence had been adduced to that effect. However, [Pearson] failed to bring that proof to the Panel. …

The Panel therefore finds that [Pearson] failed to meet the burden of proof of bad faith registration and use under Policy ¶ 4(a)(iii). …

… Therefore, the Panel finds that [Pearson] failed to support its allegations under Policy ¶ 4(a)(iii) and finds for [Automattic].

The Panel does not adopt [Automattic’s] contention that the <thesis.com> domain name is comprised entirely of a common term that has many meanings apart from use in [Pearson’s] THESIS mark. …”

So, in essence, the first of the three required elements was clearly satisfied given Pearson’s trademark rights and the second element was satisfied because Automattic had not rebutted Pearson’s case that Automattic has no rights or legitimate interests in the domain name thesis.com. It appears that Pearson hadn’t, however, adduced sufficient evidence to establish the bad faith element.

Comment on panel’s reasoning

I’d like to zoom in on two aspects of the Panel’s reasoning. The first is the Panel’s suggestion that “[Automattic’s] purchase of the <thesis.com> domain name for $100,000.00 could confer rights sufficient for Policy ¶ 4(c)(i) rights and legitimate interests, had adequate evidence to that effect been adduced”. To understand this comment, you need to know what ¶ 4(c)(i) of the UDRP says. It says this:

“… Any of the following circumstances, in particular but without limitation, if found by the Panel to be proved based on its evaluation of all evidence presented, shall demonstrate your rights or legitimate interests to the domain name for purposes of Paragraph 4(a)(ii):

(i) before any notice to you of the dispute, your use of, or demonstrable preparations to use, the domain name or a name corresponding to the domain name in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services”

With respect, in my view the suggestion that paragraph 4(c)(i) might have been found to apply here is tenuous, given the historic conflict between Pearson and Automattic’s head regarding the Thesis theme. That historic conflict must, in my view, colour the analysis of whether the name was being used in connection with a bona fide offering of goods or services. Cross-examination on this point in court proceedings could be fertile ground for a litigator. Note also that $100,000 is a lot of money to pay for an allegedly generic domain name that has no obvious connection with Automattic’s business. It would be interesting to see Automattic’s domain name inventory.

The second element of the Panel’s reasoning that I want to zoom in on is this:

“[Pearson] claims that [Automattic’s] use of the disputed <thesis.com> domain name is to divert and confuse customers and potential customers. The Panel notes that [Pearson] did not include an exhibit showing that <thesis.com> redirects to a webpage owned by Respondent. The Panel suggests that the submissions might point toward use by [Automattic] that would support findings of bad faith, pursuant to Policy ¶ 4(b)(iv) if evidence had been adduced to that effect. However, Complainant failed to bring that proof to the Panel.”

Paragraph 4(b)(iv) of the UDRP says this:

b. Evidence of Registration and Use in Bad Faith. For the purposes of Paragraph 4(a)(iii), the following circumstances, in particular but without limitation, if found by the Panel to be present, shall be evidence of the registration and use of a domain name in bad faith:

…

(iv) by using the domain name, you have intentionally attempted to attract, for commercial gain, Internet users to your web site or other on-line location, by creating a likelihood of confusion with the complainant’s mark as to the source, sponsorship, affiliation, or endorsement of your web site or location or of a product or service on your web site or location.”

According to the Panel, Pearson hadn’t adduced evidence to this effect. Had he done so, he may have succeeded. At the date of writing this post, thesis.com still redirects to themeshaper.com and let’s not forget that themeshaper.com is now an Automattic property. The left sidebar states expressly that it’s the “home to the Automattic Theme Division”.

The other point to note is that the four circumstances in paragraph 4(b) of the UDRP are not an exhaustive list of the scenarios in which bad faith might be found. If you look at the opening wording above, it says “the following circumstances, in particular but without limitation“. The listed scenarios are scenarios which will, if proved, indicate bad faith but they do not (in my view) preclude a panel from finding bad faith in other scenarios. That is the effect of the words “but without limitation”.

Other legal remedies

I noted at the outset that the UDRP dispute resolution process has it roots in contract. The registrant of a domain name agrees to submit to the dispute resolution process in its contract with the registrant.

The UDRP process is not, however, the only means by which a person can seek a remedy when feeling aggrieved by another person’s registration of a domain name that conflicts with existing trademark rights. And the fact that a complainant is unsuccessful before a UDRP panel doesn’t necessarily mean the outcome would be the same in court proceedings. Depending on the facts of a given case and the country in which a claim is brought, other remedies may lie in trademark law (for trademark infringement), tort law (for something called passing off) or fair trading or cybersquatting legislation (which exists in some countries but not others).

I make no comment on how the pursuit of such other remedies might pan out in this particular situation. For one thing there’s the fact that themeshaper.com itself isn’t overtly selling anything. At the same time, it is promoting themes on WordPress.org and, more significantly, it does link to Automattic’s commercial ventures, through the “Blog at WordPress.com” link and the Automattic image link in the footer.

Let’s wrap it up

I think I’ve said about all I want to say. As a long-time WordPress user and community observer, it has been tempting to express my own non-legal views on what’s happened here but, because I said this would be a legally oriented post, I haven’t. The only thing I’ll say is that I hope fallout management is in place because this episode seems to have reopened a rift in the WordPress community that many thought was long closed.